Immediately after Liverpool’s 1-1 draw with Everton in the Merseyside derby earlier in October, Fenway Sports Group president Mike Gordon called Brendan Rodgers to relieve him of his managerial duties. FSG sacked Rodgers a mere 8 games into the 2015/16 season. Liverpool currently sit 10th in the league after collecting a disappointing 12 points from 8 games, yet they remain only 3 points adrift of the top four and Champions League qualification.

Liverpool’s ownership group and fans have lofty ambitions for the club: they expect trophies and Champions League qualification. Liverpool chairman Tom Werner recently remarked, “Until we win more trophies we won’t be satisfied.” While Liverpool have not won the league since the 1989/90 season, they have won the Champions League as recently as 2004/05, the FA Cup in 2005/06, and the League Cup in 2011/12. Liverpool achieved a top four finish to secure Champions League qualification in all four seasons from 2005/06 to 2008/09. In other words, success is not a distant memory for Liverpool supporters.

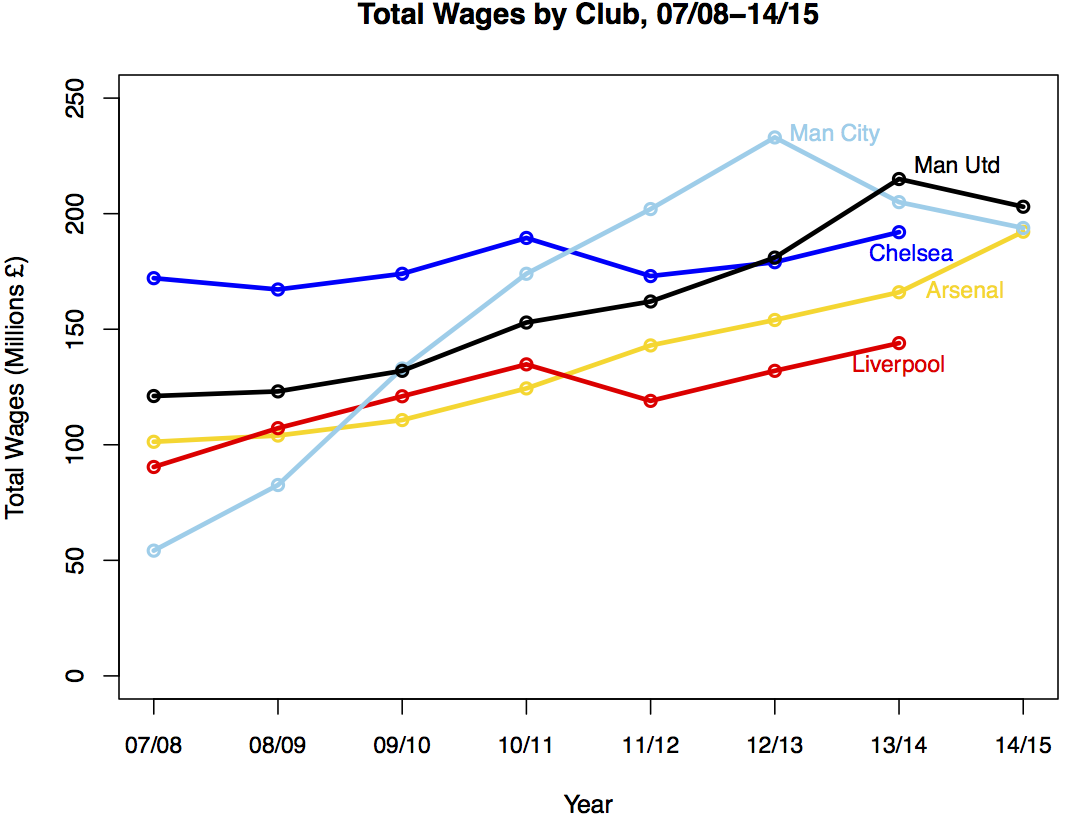

However, the financial landscape of the Premier League has changed dramatically in recent seasons. Up until the 2010/11 season, Liverpool maintained the third or fourth highest wage bill in the league. During this time period, the wage gaps between Liverpool, Arsenal, and Manchester United were minimal. Only Chelsea, owned by a Russian oligarch, had far higher wages than other Premier League clubs in this earlier period. Middle-eastern oil money soon started filling the coffers of Manchester City whose wage bill skyrocketed. At the same time, Manchester United enhanced their commercial revenue streams, providing ample funds for a higher wage bill. Arsenal too improved their financial prospects with a new stadium that increased their match-day revenue stream. While Arsenal have had this stadium during this entire period, only recently have the long-term commercial contracts required to obtain financing for the stadium started coming due. As a result, Arsenal have recently negotiated new commercial contracts boosting those revenues as well.

In recent seasons, Liverpool have struggled to keep up financially. They don’t have multi-billionaire owners willing to funnel money into the club, like Chelsea and Manchester City. They don’t have the commercial revenue potential of a “super club” like Manchester United (in spite of their somewhat successful effort to increase commercial revenues). And, they don’t have a new stadium located in a wealthy part of London like Arsenal, so they can’t dramatically increase match-day revenues (though they are expanding Anfield, which should again help somewhat). The most alarming problem for Liverpool is that they haven’t fallen behind because of financial mismanagement; they are behind in spite of entirely adequate financial management through no fault of their own.

With these recent trends in mind, it’s important to evaluate a manager based on the contemporaneous resources of a club rather than past circumstances or lofty ambitions. After accounting for the financial resources provided to Brendan Rodgers, he has overall performed about as expected or better than expected. This is not to say that Jurgen Klopp is a bad appointment. Rather, the point is simply that the decision to sack Rodgers seems extremely harsh based on the evidence.

A club’s wage bill is a very good measure of a manager’s financial resources and is highly predictive of success. Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski discuss the strong relationship between wages and performance at length in their excellent book Soccernomics. Followers of U.S. professional sports might find it strange to focus so much on teams’ payrolls. In contrast to the highly regulated world of U.S. professional sports replete with salary caps and luxury taxes, the Premier League is essentially devoid of salary regulation.[1]

A simple way to evaluate a manager’s success accounting for financial resources is to compare the club’s league position with their wage bill ranking. The figure below shows where the big five clubs—Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, and Manchester United—finished in the league table over the past three seasons and the ranking of their wage bill. Black dots indicate position in the league table at the end of the season and the red circles indicate wage bill ranking.[2] Brendan Rodgers’ Liverpool finished two spots below their wage ranking in his first season, three spots above in his second season, and one spot below in his third season. Rodgers’ 2011/12 Swansea had the lowest wage bill in the league, yet achieved an impressive 11th place finish. Based on this analysis, Rodgers on average performed at expectations in his three seasons at Liverpool and above expectations in his season at Swansea.

League position is not a very precise measure of success as multiple teams can accrue nearly the same amount of points over the course of a season, and they will all finish a different place in the table. Similarly, wage ranking merely indicates the ordering rather than the size of the gaps in wage bills between clubs. Thus, I also consider the relationship between wage bill and total points earned in a season. Given that the distribution of Premier League wage bills has changed over time (both in terms of mean and variance), I standardize the log wage bills of each club by season to make them more comparable. This means that for each season this measure has a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. The important thing to understand is that a positive value indicates that a club’s wage bill is above the average of that season, and a negative value indicates a wage bill is below the average of that season.

Based on the figure below, it is clear that the relationship between points and wages is strong and positive. I include a line of best fit, which indicates the “expected” points for clubs given their wage bills. Rodgers’ Liverpool in 2013/14 performed far better than expected based on the club’s financial resources. His two other seasons at Liverpool were slightly worse than expected. His 2011/12 Swansea also dramatically outperformed expectations. In contrast, Liverpool performed far worse than expected in the three seasons prior to Rodgers’ appointment given their financial resources.

The figure below shows the number of points a club is expected to earn in each season based on their financial resources vs. how many points the club actually earned. The red bars indicate how many points a club is expected to accrue based on their wage bill that season, and the black bars indicate how many points a club actually accrued in that season. In seasons that a club outperforms expectations the black bars are higher than the red bars. In Rodgers’ first and third seasons at Liverpool, he accrued about 6 points less than expected. While not above the expected number of points given Liverpool’s wage, these performances are not especially far below this expectation. In his second season at the club, he earned a whopping 16 points more than expected. In his single season at Swansea, he outperformed expectations by 12 points. On average, Rodgers’ teams have earned about 4 points more than expected given their financial resources in his 4 Premier League seasons.

What of the often-quoted £300m investment in player purchases over the course of Rodgers’ tenure? It is important to note that the wage measure used in this analysis largely accounts for transfer spending: a club’s wage bill increases as the club purchases additional higher-quality players who likely require high wages. Seldom does a club pay a high transfer fee and low wages for a player. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that Liverpool also sold two of its best players, Luis Suárez and Raheem Sterling, during Rodgers’ tenure. For the three full seasons of Rodgers’ reign at Liverpool, 2012/13, 2013/14, and 2014/15, Liverpool’s net transfer spending (total player sales subtracted from total player purchases) was lower than Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City, and Manchester United. This is not to argue that Liverpool spent the proceeds from player sales wisely, but rather to suggest that Rodgers was at resource disadvantage in terms of both transfer spending and wages.

Despite the above evidence that Rodgers performed near or above expectations in all three seasons at Liverpool, there is still reason to think Klopp is an excellent fit for the manager position at Liverpool. While manager of Borussia Dortmund in Germany’s Bundesliga, Klopp managed to win the league in back-to-back seasons in 2010/11 and 2011/12. He achieved this impressive feat despite a massive financial gap between Dortmund and super club Bayern Munich. Bayern’s wages are nearly double those of Dortmund. In other words, Klopp is a manager who has achieved success by extracting much from few financial resources.

While the financial gap between Liverpool and the other top English clubs is smaller than the Dortmund-Bayern gap, Klopp may nevertheless find it more difficult to win trophies in England. Most clubs, even those with vast financial resources, periodically have bad seasons. For instance, Manchester United underperformed the past two seasons based on their financial resources. If it were only Manchester United in the picture, Liverpool could take advantage of those down years. Klopp did exactly this while at Dortmund. When Dortmund won the league in back-to-back seasons, Bayern accumulated 65 and 73 points in those seasons. In the subsequent season, Bayern accrued an impressive 91 points. However, the situation in the Premier League is dramatically different from the Bundesliga; four clubs have a non-negligible financial advantage over Liverpool. It is highly unlikely that the down years of these four clubs will coincide. This is not to say that Klopp can’t achieve success at Liverpool, but winning the Premier League may prove more difficult than the Bundesliga.

[1] To some extent, UEFA, the European confederation’s governing body of soccer, has tried to limit the financial losses that clubs’ are permitted through Financial Fair Play rules. However, these restraints maintain (and perhaps entrench) financial disparities between clubs, as spending restrictions are set based on clubs’ revenues.

[2] Only Arsenal , Manchester City, and Manchester United have released financial statements for 2014/15, so I assume wage bills do not change between 2013/14 and 2014/15 for all analyses.